Revolutionary by Nature: Master Prints by Women Artists 1896-2020

Beginning in 1896, this selection of works looks at images of women as depicted by other women, breaking free of the prevailing paradigm of gender stereotypes, ornamental beauty or sexual “otherness.” Throughout this selection of works, the woman’s body is free of objectification and the eroticized prism through which it has largely been considered for much of art history. Filling the diverse roles of advocate, destructor, creator, innovator, mother, and citizen, the seminal figure of the woman takes center stage in this survey of prints by women artists.

The mediums represented in the exhibition include etching, serigraph, silkscreen, drypoint, lithography, aquatints and woodcuts. Surveying a wide variety of interests, backgrounds and social climates, this selection of works follows a century’s worth of art made by women following Mary Cassatt’s simple principle that “women should be someone, not something.”

Color drypoint and aquatint Image: 13 x 16 7/8 inches (33 x 42.9 cm) Paper: 16 5/8 x 19 3/4 inches (42.2 x 50.2 cm)

Mary Cassatt made pictures of women that aligned with her belief that, as she put it, “women should be someone, not something.” As one of the few female (and only American) artists in the French Impressionist movement, her work distinguished itself in that she considered and depicted women as complete within themselves—individuals existing beyond the limits of male appreciation and bodily sensuality. Cassatt is best known for her paintings and prints of the daily lives and intimate bonds shared by women and children.

By the Pond features a specific mother and son duo who appear in two other prints by Cassatt—Under the Horse Chestnut Tree and The Barefooted Child. Oblivious to the outside world, the mother is fully engrossed in her child. Her son, characterized by a distinctively ruddy face and curly hair, looks away, seemingly pensive.

Also titled Mother and Child before a Pool and Young Motherhood, By the Pond is Cassatt’s most ambitious color print as well as her largest and most painterly. The color in each impression varies as the artist manipulated the inks in a monotype-like fashion. This is especially apparent in the lush blues and greens of the pond, printed à la poupée. Her remarkable use of drypoint is evident in the handling of the young mother and son’s faces. In this work, Cassatt paid special attention to the subtle modeling of flesh—an approach more reminiscent of her paintings or pastels.

Known for her great sense of wit, long-time Greenwich Village resident Mabel Dwight made her first print in 1927, at the age of fifty-two. From there, she went on to produce a body of lithographic works that distill the political and popular culture of the late 1920s and 1930s.

In this lithograph, Dwight depicts the burlesque dancer as she is seldom seen in the arts. In this scene, set at Minsky’s National Winter Garden in Manhattan’s lower east side, the dancer is depicted as a towering figure, looking down on a crowd of humorously enraptured men. According to art historian Helen Langa, “Her print suggests the woman’s pleasure in her own sexual performance”—an absolute taboo in the 1920s. This view of the nude female form is remarkably different from the ways in which sexuality was traditionally defined, in which a woman’s sexuality is tacked on to her by the male viewer. In this work, it is the burlesque dancer who is in control of the unfolding situation, who commands attention, and defines her own sexual presence. It is the men in the room—comically shocked, ludically titillated—who are “other” in this lithograph.

Lithograph, Image: 9 3/4 × 7 15/16 inches (24.8 × 20.2 cm), Paper: 16 × 11 1/2 inches (40.6 × 29.2 cm), Edition of 50

Color etching with aquatint and accompanying pochoir stencils, watercolor, tracing and drypoint, Image: 6 1/2 x 6 inches (16.5 x 15.2 cm), Only known impression

Like many of the women who were part of the interwar Provincetown artist colony, Maud Hunt Squire lived her life on the frontier of radical modernism and progressive feminism. She and her life-long partner Ethel Mars belonged to a generation of women artists who built their careers as expatriated Americans in France and helped push the boundaries of woodblock prints in Provincetown. Her early prints in Paris denote the influence of Mary Cassatt, whose studio neighbored Squire’s in Paris. Mars and Squire’s own collection included a Cassatt color etching. Squire’s vignettes of French urban life are graphically bold and witty, with a “fresh, transparent look like that of watercolor,” according to April Kingsley.

This Parisian color etching captures the full force of the modern, liberated lifestyle that she and Mars first discovered in the French capital and would carry on for the rest of their lives. The etching’s fashionably dressed woman with orange hair and bright lipstick exudes the kind of cosmopolitan life that the artist Anne Goldthwaite, a friend of Mars and Squire’s, noted on upon visiting them in Paris, six months after their arrival:

“Miss Mars had acquired flaming orange hair and both were powdered and rouged with black around the eyes until you could scarcely tell whether you looked at a face or a mask,” Goldthwaite wrote in her autobiography. “The ensemble turned out to be very handsome, and their conversation, in public that is, became bloodcurdling. I went with them to the cafe where they pre-empted seats in the best corner, never drank but one cafe crème for eight sous and gave two sous pourboire. They paid their debts and in private led exemplary lives. I hope they will never read this last statement, as they would think I was offering them an insult—breaking down the legend they have laboriously built up!”

Woodcut, Image: 14 x 13 inches (35.6 x 33 cm), Paper: 15 1/2 x 18 inches (39.4 x 45.7 cm), Edition of 150

In this 1928 woodcut, Käthe Kollwitz represents a biblical scene in which the virgin Mary goes to visit her cousin Elisabeth. According to Christian scripture, the two women are with child, and upon greeting Mary, Elisabeth is filled with the Holy Spirit and her baby leaps in her womb.

Kollwitz was first struck by the imagery of Elisabeth and Mary upon seeing a fifteenth century painting by Konrad Witz in which Mary and Elisabeth appear in the corner of the canvas, sumptuously dressed, standing at a respectable distance from one another. The motif of these two women stayed with Kollwitz for six years. During this time, Kollwitz lost her son in the First World War and was confronted to the extreme social conditions of interwar Germany, including rising levels of fascism, devastating levels of poverty and squalid living conditions for women and children in particular.

In 1928, Kollwitz returned to the story of Mary and Elisabeth with a vastly different attitude than that of Witz. The two women depicted here are devoid of the overwhelming sense of joy described in the Biblical verse. Instead, they stand, somber, dressed humbly like 1920s-era factory women workers. There is no longer a question of respectable space between them, as Elisabeth tenderly places a hand on Mary’s abdomen, wraps her other arm around her cousin’s shoulder and whispers something in her ear. To create this print, Kollwitz used a soft wood which enabled her to create strikingly crisp details on the women’s fingers and necks. In this print, we are no longer assisting a scene of splendor but one of resilience and tender female companionship.

Over a period dating from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, May Stevens produced over seventy works exploring the parallels between Stevens’ mother, Alice Stevens, and Rosa Luxemburg, a Polish-German Marxist philosopher, prolific writer, and activist whose legacy includes co-founding the German Communist Party, and whose brutal murder in 1919 is commemorated to this day. Stevens produced some thirty collages, thirteen drawings, a handful of prints, and approximately fourteen paintings that endeavored to celebrate and validate both women for who they were.

In this serigraph, under various images of her mother and the woman Stevens sometimes referred to as her “spiritual mother,” she wrote, “Rosa Luxemburg, politician, revolutionary theoretician and leader, murder victim (1871-1919). Alice Stevens, mother, housewife, ironer and washer, inmate of hospitals and nursing homes (born 1895). Ordinary. Extraordinary.”

Serigraph, 30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.9 cm), Edition of 36

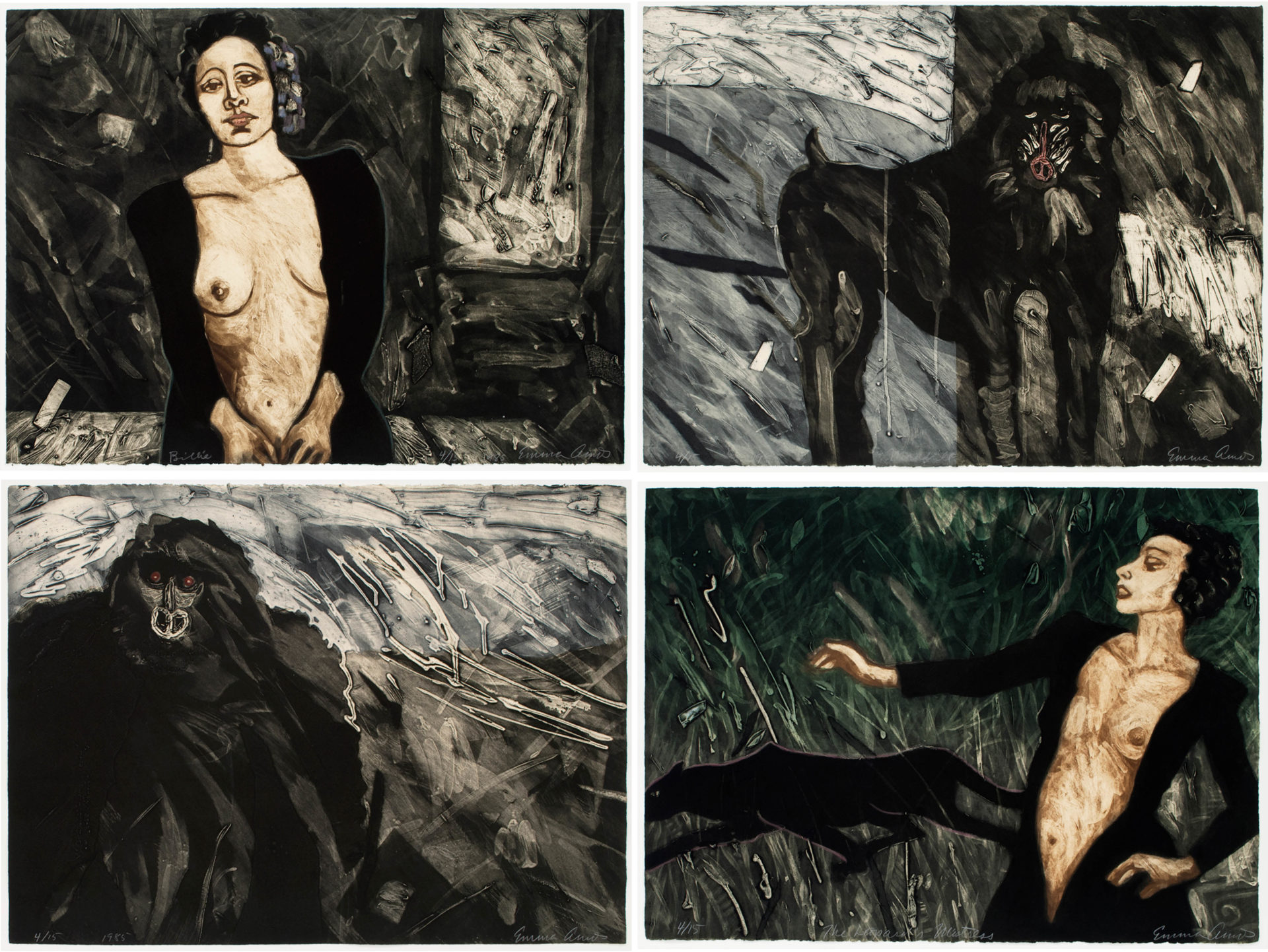

Set of 4 intaglio printed silk collagraphs, 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm) each, Edition of 15

In her work, Amos frequently depicted black performers juxtaposed with wild animals—thus eyeing the fleeting and illusory power, both in physicality and influence, of the black celebrity. “I want to make clear the relationships between artists, athletes, entertainers, and thinkers, and the prowess, ferocity, steadfastness, and dynamism of animals,” Amos told Lucy Lippard in 1989. Her transformative investigation into the depictions of the black body further extends to her representation of Josephine Baker, an important subject for the artist. The French-American icon, who was politically vocal and arguably the most visible black entertainer of her time, figured as a new way to reconstruct blackness.

Baker, who in fact owned various jungle animals, is represented in the bottom right vignette of this print while Billie Holiday is represented in the top left vignette. They are both depicted nude and juxtaposed with wild animals in order to evoke the grace, beauty and strength of both figures. In this work, Amos attempts a revisionist take on the nude, suggesting not exotic sexuality but vulnerability. The motif of a nude black woman is one with which Amos struggled, and this print is the only work in her oeuvre in which a black woman is depicted naked. “I did not want to see black women with no clothes on,” she said in 1995. “It means something else when a black woman has no clothes on… It means you are for sale.”

Drypoint on Somerset Satin paper

46 7/8 x 36 7/8 inches (119.1 x 93.7 cm)

Edition of 50

One of Bourgeois’ most important prints, this work can be seen as a monumental self-portrait by Louise Bourgeois, representing the pain that she experienced throughout her life from personal attacks. Bourgeois references the Christian martyr, Saint Sebastian, a famous subject in the history of art and literature. Saint Sebastian has been portrayed by artists as varied as Durer, Titian, El Greco, Mantegna, Daumier and Egon Schiele.

Saint Sebastian is traditionally portrayed as a handsome young man, shot with arrows against a tree. Here, Bourgeois creates Sainte Sébastienne in a female form, whose flesh seems to be made of wooden rings. According to the artist, “She is aware of the hostility somewhere. The arrows are from the outside… they are not inner… this is not stress. She is bewildered by what happened… she does not know what to do. When you get angry you become ugly… you lose your hair. The profound effect of the arrows… the sharp criticism… makes her defensive. The state of defensiveness makes her self-criticizing, self-destroying, self-mutilating. Cutting your hair… that is the equivalent of cutting off your head… it is masochistic. Then you are not desirable.”

Kiki Smith is a radically inventive artist whose transgressive early works confronted mortality and bodily decay, while her more recent work on paper explores the animal kingdom, the natural world and portraiture. Printmaking became an essential part of Smith’s practice during the mid-1980s, and she persistently pushes the medium’s boundaries not only of style, technique,and imagery but also between print, drawing, and book.

To create the hand colored photogravure and lithograph My Blue Lake, Smith used the British Museum’s 360-degree periphery camera to take an encompassing self portrait. After spending two days photographing her body as if it were a terrain, Smith used one of the resulting four-by-five-inch negatives to make an enlarged photogravure. In this print, Smith blends her features into landscape, transforming her skin into a lake and her hair into mountains or shore. Like the environment they inhabit, women’s bodies are in a state of constant flux and in My Blue Lake, Smith turns the body into a literal landscape. The hair varies in each impression as it is hand-colored à la poupée.

Photogravure with a la poupée inking and lithograph, on mould-made En Tout Cas paper, 43 3/4 x 54 3/4 inches (111.1 x 139.1 cm), Edition of 41

Set of six woodcuts, 12 x 10 inches (30.5 x 25.4 cm) each, Edition of 20

Arcade Suite features as a reworking of a number of themes found in Alison Saar’s sculptural work. Working in black, red and white, Saar depicts six lone figures, each serving as different studies of body, gender and race. In one, a woman peers into a mirror and a white face looks back at her. In another, the body of a woman comes together in the cigarette smoke of a fedora-wearing dandy. A severed head floats in a third woodcut, with an anatomical representation of a heart next to it. In a fourth print, a naked woman tilts her head onto her shoulder, contorted under the rain. Each figures’ eyes are empty, casting an eerie light on these works, suggesting that the viewer is not looking at people but at masks.

Most of the figures in Saar’s works are women—featuring not only as feminist icons but, according to art historian Nancy Doll, “powerful bearers of dignity, self-determination, plight and abuse.”

The titles of these works are, in order:

Hand to Mouth, Heart, Heart, Heart, Red Girl, Mirror, Rose Tattoo, and Man with Hat.

Silkscreen in 9 colors, 24 x 20 inches (61 x 50.8 cm), Edition of 75

Deborah Kass is a multidisciplinary artist examining the interactions of politics, pop culture, art history, and identity within a Pop art sensibility. Interested in ideas of appropriation and duplication, Kass works in a variety of media, including painting, prints, neon, sculpture, and installation. She blends together gender issues, feminism, and a keen sense of humor. Her art is geared to challenge contemporary gender norms and male-centric social structures. Throughout her career, the artist has championed feminist agendas within the art world and beyond.

In the 1990s, Kass embarked on the re-imagining of Andy Warhol’s oeuvre, a project that would occupy her for several years. A passionately feminist artist, Kass recreated Warhol’s most famous works with a pointedly woman-oriented slant. By appropriating Warhol’s work, Kass annexes the artistic gravitas implied by one of the most influential artists of the postwar period. She replaces Warhol’s series of celebrity muses with a selection of her own personal heroines, and by doing so, she alters the gaze cast upon these subjects. These celebrity figures are no longer passive muses but active artistic women with achievements of their own. Kass therefore flips the script implied by Warhol’s hugely influential series.

“In my own work I replace Andy’s male homosexual desire with my own specificity: Jew love, female voice, and blatant lesbian diva worship,” Kass has explained.

In this work, Kass co-opts supplants Barbra Streisand’s face in Warhol’s famous Jackie Onassis series.